|

Joan of Arc (French:

Jeanne d'Arc;

is a national heroine of France and a Catholic

saint. A peasant girl born in eastern France,

Domrémy, to Jacques

d'Arc and Isabelle Romée. Her parents owned about 50

acres of land and her father supplemented his

farming work with a minor position as a village

official, collecting taxes and heading the town

watch.

Jeanne asserted that she had visions from God

that told her to recover her homeland from English

domination late in the Hundred Years' War.

|

|

|

|

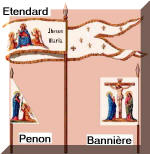

Pennant of Jeanne

which was never found |

Sword of Jeanne d'Arc |

The French king at the time of Joan's birth,

Charles VI, suffered

bouts of insanity and was often unable to rule. The

king's brother Duke Louis

of Orléans and the king's cousin

John the Fearless,

Duke of Burgundy,

quarreled over the regency of France and the

guardianship of the royal children. This dispute

escalated to accusations of an extramarital affair

with Queen Isabeau of Bavaria

and the kidnappings of the royal children. The

matter climaxed when the Duke of Burgundy ordered

the assassination of the Duke of Orléans in 1407.

The factions loyal to these two men became known

as the Armagnacs and

the Burgundians. The

English king, Henry V,

took advantage of this turmoil to invade France,

winning a dramatic victory at

Agincourt in 1415, and capturing northern

French towns. The future

French king,

Charles VII,

assumed the title of Dauphin

as heir to the throne at the age of 14, after all

four of his older brothers died.His first

significant official act was to conclude a peace

treaty with Burgundy in 1419. This ended in disaster

when Armagnac partisans murdered

John the Fearless

(Jeans-sans-Peur)

during a meeting under Charles's guarantee of

protection. The new duke of Burgundy,

Philippe

le Bon,

blamed Charles and entered into an alliance with the

English. Large sections of France were conquered.

By the beginning of 1429, nearly all

of northern France and some parts of the southwest

were under foreign control. The English ruled Paris,

while the Burgundians controlled Reims. The latter

city was important as the traditional site of French

coronations and consecrations, especially since

neither claimant to the throne of France had yet

been crowned. The English had laid siege to Orléans,

which was the only remaining loyal French city north

of the Loire. Its strategic location along the river

made it the last obstacle to an assault on the

remainder of the French heartland. In the words of

one modern historian, "On the fate of Orléans hung

that of the entire kingdom.

No one was optimistic that the city could

long withstand the siege.

|

|

|

|

|

Sketch representing Joan of Arc,

in a

register of the Parliament of Paris

by Clerk Clément

de Fauquembergue |

Journey of Jeanne to

Chinon

to meet the Dauphin |

Jeanne

d'Arc enters Orléans

painting by

Jean

Jacques SCHERRER, 1887. |

The uncrowned King Charles VII sent her to the siege

at Orléans as part of a relief mission. Joan of Arc arrived at the siege of Orléans

on 29 April 1429. She

gained prominence when she overcame the

dismissive attitude of veteran commanders and

lifted the siege in only nine days.

She overcame this by disregarding the veteran commanders' decisions,

appealed to the town's population, and rode out to each skirmish, where she

placed herself at the extreme front line, carrying her banner. Several more

swift victories led to Charles VII's coronation at Reims

and settled the disputed succession to the throne.

She

led the French army to several important victories

during the Hundred Years' War, claiming divine

guidance.

|

|

|

|

|

Jeanne d'Arc

and King Charles VII |

Jeanne d'Arc

Siege of Orléans |

Jeanne d'Arc

|

After minor action at La-Charité-sur-Loire in

November and December, Joan went to Compiègne the

following April to defend against an English and

Burgundian siege. A reckless skirmish on 23 May 1430

led to her being captured. When she ordered a

retreat, she assumed the place of honor as the last

to leave the field. Burgundians surrounded the rear

guard, she was unhorsed by an archer and initially

refused to surrender.

The English government eventually purchased

her from

Jean de Luxembourg for ten thousand écus - to be

tried by an ecclesiastical court.

Joan's trial for heresy was politically motivated.

The duke of Bedford claimed the throne of France for

his nephew Henry VI. She was responsible for the

rival coronation. Condemning her was an attempt to

discredit her king. Legal proceedings commenced on 9

January 1431 at Rouen, the seat of the English

occupation government. The procedure was irregular

on a number of points.

To summarize some major problems, the jurisdiction

of judge Bishop Cauchon was a legal fiction. He owed

his appointment to his partisanship. The English

government financed the entire trial. Clerical

notary Nicolas Bailly, commissioned to collect

testimony against her, could find no adverse

evidence. Without this, the court lacked grounds to

initiate a trial. Opening one anyway, it denied her

right to a legal advisor.

The trial record demonstrates her exceptional

intellect. The transcript's most famous exchange is

an exercise in subtlety. "Asked if she knew she was

in God's grace, she answered: 'If I am not, may God

put me there; and if I am, may God so keep me. The

question is a scholarly trap. Church doctrine held

that no one could be certain of being in God's

grace. If she had answered yes, then she would have

convicted herself of heresy. If she had answered no,

then she would have confessed her own guilt. Notary

Boisguillaume would later testify that at the moment

the court heard this reply, "Those who were

interrogating her were stupefied" and abruptly

halted the questioning for that day. This exchange

would become famous, and is incorporated into many

modern works on the subject.

Several court functionaries later testified that

significant portions of the transcript were altered

in her disfavor. Many clerics served under

compulsion, including the inquisitor, Jean LeMaitre,

and a few even received death threats from the

English. Under Inquisitorial guidelines, Joan should

have been confined to an ecclesiastical prison under

the supervision of female guards (i.e., nuns).

Instead, the English kept her in a secular prison

guarded by their own soldiers. Bishop Cauchon denied

Joan's appeals to the Council of Basel and the Pope,

which should have stopped his proceeding.

|

|

|

|

|

Castle of

Rouen |

Tower in Rouen - where

she might have been imprisoned |

|

The twelve articles of accusation that summarize the

court's finding contradict the already-doctored

court record. Illiterate Joan signed an abjuration

document she did not understand under threat of

immediate execution. The court substituted a

different abjuration in the official record.

Heresy was a capital crime only for a repeat offense.

Joan agreed to wear women's clothes when she

abjured. A few days later, according to

eyewitnesses, she was subjected to an attempted rape

in prison by an English lord. She resumed male

attire either as a defense against molestation or,

in the testimony of Jean Massieu, because her dress

had been stolen and she was left with nothing else

to wear.

Eyewitnesses described the scene of the execution on

30 May 1431. Tied to a tall pillar, she asked two of

the clergy, Martin Ladvenu and Isambart de la

Pierre, to hold a crucifix before her. She

repeatedly called out "in a loud voice the holy name

of Jesus, and implored and invoked without ceasing

the aid of the saints of Paradise." After she

expired, the English raked back the coals to expose

her charred body so that no one could claim she had

escaped alive, then burned the body twice more to

reduce it to ashes and prevent any collection of

relics. They cast her remains into the Seine. The

executioner, Geoffroy Therage, later stated that he

"...greatly feared to be damned for he had burned a

holy woman.

Jeanne d'Arc was burned at

the stake 30 May 1431

nineteen years old.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Rouen

place where Jeanne died |

|

location where Jeanne died |

|

Twenty-four years later, on the initiative of

Charles VII, who could not possibly afford being

seen as having been brought to power with the aid of

a condemned heretic, Pope Callixtus III reviewed the

decision of the ecclesiastical court, found her

innocent, and declared her a martyr.

She was beatified in 1909 and later canonized

in 1920. She is one of three patron saints of France.

Joan of Arc was not a feminist. She operated within

a religious tradition that believed an exceptional

person from any level of society might receive a

divine calling. She expelled women from the French

army and may have struck one stubborn camp follower

with the flat of a sword. Nonetheless, some of her

most significant aid came from women. King Charles

VII's mother-in-law,

Yolande of Aragon, confirmed

Joan's virginity and financed her departure to Orléans. Joan of Luxembourg, aunt to the count of

Luxembourg who held custody of her after Compiègne,

alleviated her conditions of captivity and may have

delayed her sale to the English. Finally, Anne of

Burgundy, the duchess of Bedford and wife to the

regent of England, declared Joan a virgin during

pretrial inquiries.For technical reasons this

prevented the court from charging her with

witchcraft. Ultimately this provided part of the

basis for her vindication and sainthood. From

Christine de Pizan to the present, women have looked

to her as a positive example of a brave and active

female. |